The “Trilogy of Life,” for all of its flaws, brought Pier

Paolo Pasolini a great deal of acclaim and a relatively high amount of

commercial success late in his career.

But the eternally provocative writer-director gradually grew disenchanted

with the trilogy’s optimistic and hopeful view of the world as a playground of

art and sex. Around the time of the

release of Arabian Nights (1974) Pasolini

denounced the worldview expressed in his own trilogy in an Italian newspaper. In an essay entitled Abjuration from “The Trilogy of Life,” Pasolini wrote:

Even the “reality” of innocent bodies has been

violated, manipulated, submitted to the consumerist power: or rather, this violence on bodies has become

the most macroscopic datum of the new human epoch…Private sexual life (such as

my own) has undergone both the trauma of false tolerance and of corporal

degradation; and in sexual fantasies what was once pain and joy has become

suicidal disappointment, formless sloth…

Therefore, I am adapting myself to the degradation, and

I am accepting the unacceptable. I am

maneuvering to reorganize my life. I am

forgetting how things were before. The

beloved faces of yesterday are beginning to fade. I am – slowly and without alternatives –

confronted with the present.

This matter-of-factly hopeless and despairing viewpoint

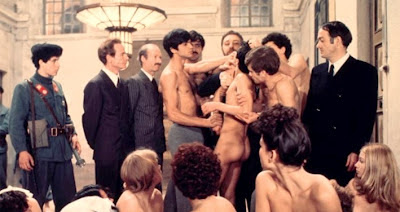

animates every frame of Pasolini’s final film, Salo (1975), a simultaneous adaptation of Dante’s Inferno and the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom, and set in the last

days of Mussolini’s Italy. You might

expect a film with this pedigree to hold something back, to avoid graphically

depicting the atrocities described in Dante and de Sade’s literary works. But Salo

holds precisely nothing back – the film is essentially an uninterrupted succession of

scenes in which a group of powerful fascists torture, rape, humiliate,

mutilate, and/or kill a group of very young looking men and women. These acts occur almost uniformly in the

direct center of the frame of Pasolini’s shot compositions, which, in a

surprising but effective rebuke of his standard rough verite style are

generally cold and static, essentially forcing the viewer to take the

perspective of the fascists. Pasolini

intended for the film to be “indigestible,” and indeed it is extremely difficult

to stomach; chapter headings such as “Circle of Blood” and “Circle of Shit”

aren’t metaphors. Knowing that the

actors are actually eating brownies when their characters are supposed to be

eating huge amounts of feces (in one of the film’s most notorious scenes) doesn’t

make the scene any easier to take. The

nonstop degradation is occasionally punctuated by strikingly incongruous and

weirdly sinister moments of physical comedy that have the exact opposite effect

of “comic relief” and only make the film more disturbing. There are also some creepy and haunting

ambiguous moments, such as a scene where one of the fascists’ wives

inexplicably jumps out of a fourth story window.

No one has ever made or will ever make a movie as horrifying

and troubling as Salo. There are a lot of films that have

provocative subject matter or grisly, realistic looking violence, but it’s

impossible to imagine one that stares directly into the heart of darkness to

the extent that Pasolini’s final film does.

Many films are disturbing; Salo

is emotionally scarring. I can’t imagine

anyone sitting through the entirety of Salo

without at least once covering their eyes or getting literally sick to their

stomach, and personally I can’t imagine watching the film more than once in a

lifetime. I virtually always rewatch a

film that I’ve already seen if I’m going to write about it for this blog, but I

had to make an exception in this case.

Though I’m basing what I write here on four-year old memories, Salo has left a mark on me that will

make it hard to forget. It’s the only

film that I’ve seen that I think of as a genuinely traumatic experience.

Ironically, the very things that make Salo unwatchable are also what make it brilliant, and possibly the

greatest achievement of Pasolini’s career.

The director’s strategy of distancing the viewer from the nameless victims

and putting us in the cold, voyeuristic perspective of the fascist torturers

initially seems offensive, but Pasolini’s moral goal (and lunatic ambition)

with this film seems to be to beat the latent fascism out of each viewer. Salo

takes the desire (that we all have on some level) to have power over another

human being and pushes it to its logical extreme, using Brechtian distancing

effects to present our lopsided societal structure in its most base and disgusting

light. The film refuses to allow us to

redeem ourselves, even through Pasolini’s most cherished social causes. A victim who gives the Communist salute is

gunned down mercilessly; another one praying to God is forced to literally eat

shit. Instead of coming to any real

resolution, Salo ends mysteriously

with two male victims waltzing together, leaving the prior violence hanging in

the air. It’s a relentlessly disturbing

experience, and a profoundly uncompromising end to one of the cinema's most philosophically complex

filmographies.

FINAL GRADES FOR PIER

PAOLO PASOLINI

Accattone (1961) = B

Mamma Roma (1962) = B+

La ricotta (short) (1963) = B+

The Gospel According to Matthew (1964) = A-

Hawks and Sparrows (1965) = B-

Oedipus Rex (1967) = B+

Teorema (1968) = B

Porcile (1969) = D+

Medea (1969) = C+

The Decameron (1971) = C+

The Canterbury Tales (1972) = C

Arabian Nights (1974) = B+

Salo (1975) = A-