Each film on the following list was available

(whether in theatres, on DVD, or through streaming) to see in the Milwaukee

area for the first time in 2013. Due to

the vagaries of international film distribution, some of these films were

released in other areas of the world in 2012 (which explains how two of the

films in my top 10 were nominated for Best Picture at last year’s Academy

Awards despite not being released in Wisconsin until January) and some won’t be

released in other places until 2014, but for the purposes of this list these

are 2013 releases since they were the ones that I had a reasonable opportunity

to see for the first time this year.

Before getting to the main list, here are some quick lists explaining

why certain notable films didn't make the cut.

Movies that I really

want to see that I missed

Barbara (Christian Petzold, Germany, 105 min.)

Blue is the Warmest Color (Abdellatif Kechiche, France, 179

min.)

A Hijacking (Tobias Lindholm, Denmark, 103 min.)

Mud (Jeff Nichols, USA, 130 min.)

Tabu (Miguel Gomes, Portugal, 118 min.)

Wadjda (Haifaa Al-Monsour, Saudi Arabia, 98 min.)

Movies that I really want

to see that haven’t yet made it to the Milwaukee area

Camille Claudel 1915 (Bruno Dumont, France, 95 min.)

Her (Spike Jonze, USA, 126 min.)

Night Moves (Kelly Reichardt, USA, 112 min.)

Only Lovers Left Alive (Jim Jarmusch, USA, 123 min.)

The Past (Asghar Farhadi, France/Italy, 130 min.)

The Wind Rises (Hayao Miyazaki, Japan, 126 min.)

A Masterpiece

1) The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer,

Denmark/Norway/UK, 116 min.)

The most mesmerizing, terrifying, and all-around audacious

movie of the year is documentarian Joshua Oppenheimer’s unblinking look at the

very worst of humanity. In 1965 and ’66

the Indonesian military staged a coup in which they exterminated the nation’s

Communist party (and anyone who they may have arbitrarily decided was a

Communist). Rather than being punished

for their war crimes, many of the perpetrators have remained major players in

the Indonesian political structure, and are even celebrated as heroes by the

country’s media. The provocative hook of

Oppenheimer’s film is that he has encouraged these criminals to recreate their

atrocities in the style of the Hollywood movies that they love. Even while attempting to portray themselves

as heroes, the self-described “gangsters” inevitably end up exposing themselves

as vicious thugs, and much of the film’s queasy fascination lies in the way

that these recreations make some of these men become self-aware of their

awfulness for seemingly the first time.

In the film’s unforgettable conclusion, one of these fearsome killers,

having portrayed the role of a victim in one of the reenactments, is reduced to

a pathetic dry-heaving shell that couldn’t be further from the macho action

hero that he’s always imagined himself as.

A- Excellent

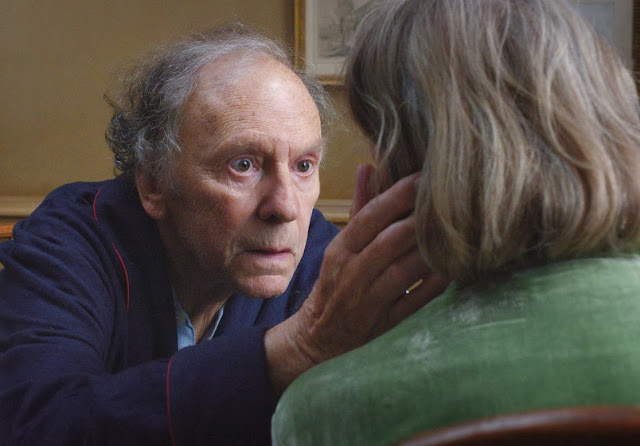

2) Amour (Michael Haneke, France/Austria, 127

min.)

Acclaimed Austrian director Michael Haneke’s best film to

date is an unblinkingly realistic look at the way that human bodies inevitably

fall apart as they get closer to death.

In past films Haneke has exaggerated the cruelty of human beings (and/or

the universe) in order to make stern points about our capacity for destruction,

but here he seems mostly interested in testing the limits of an elderly

couple’s lifelong love as they deal with extremely stressful

circumstances. French New Wave legends

Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva believably portray the relationship, which makes their attempts to hold on to their dignity as the

latter deals with a debilitating stroke all the more devastating.

3) The Wolf of Wall Street (Martin

Scorsese, USA, 179 min.)

The trailers for Martin Scorsese’s latest film promised an

over-the-top, adrenaline-fueled black comedy about outrageous excess. The actual movie somehow sustains the

intensity of the preview footage for a full three hours, matching the pumped-up

bravado of criminal stock salesman Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio) with an

epic series of outrageous, vividly staged scenes of unchecked bacchanalia. Scorsese doesn’t shy away from reveling in

the stockbrokers’ amoral behavior, but he slowly turns their unsustainably

corrupt business model into a nightmare, climaxing in a darkly hilarious

Quaalude freak-out that is a tour de force for both DiCaprio’s marvelously outsized

performance and Scorsese’s kinetic filmmaking.

4) Computer Chess (Andrew Bujalski, USA, 92

min.)

Despite the fact that it’s set in the early ‘80s, and was

filmed (or, rather, taped) on primitive tube cameras, Computer Chess feels like the freshest movie of the year, the one

that’s least indebted to the films of the past and most open to the wide range

of possibilities of the medium. The

large ensemble cast (made up of a mix of professional actors and old-school

computer experts) is gathered together for a computer chess tournament, but

director Andrew Bujalski treats that basic premise like a science experiment, isolating certain

participants and forcing them to mingle with a New Age group that is having a

conference at the same hotel as the tournament, having others interact

uncomfortably with the rare female presences at the tournament, and following

one ornery computer programmer (Myles Paige) whose room reservation was lost as

he has surreal experiences in the hotel’s hallways. The “action” of the computer chess tournament

is hilariously deadpan, but the film is equally interesting when the narrative

incorporates conspiratorial and science-fiction elements, or when Bujalski

indulges in odd experimental tangents that test the tube camera’s various

settings. Bujalski had already established himself as a

talented artist with films like Funny Ha

Ha (2003) and Mutual Appreciation

(2005), but Computer Chess represents

a quantum leap in ambition. It’s a truly

singular experience.

5) Beyond the Hills (Christian Mungiu,

Romania, 150 min.)

In a monastery so shut off from the modern world that

automobiles stick out like UFOs, Voichita’s (Cosmina Stratan) quiet life of

worship is disrupted by the arrival of lifelong friend (and apparent lover)

Alina (Cristina Flutur). Emotionally

fragile and frustrated by her best friend’s new lifestyle, Alina embodies

real-world problems that the facility’s priest (Valeriu Andriuta) can only

think to deal with in one way – by performing an exorcism. The resulting tragedy might have played out

as a simple anti-religious screed, but writer-director Christian Mungiu is

after something much more complicated: a

layered tableau of personal and institutional miscommunications in which forces

secular and religious, political and personal, are constantly talking past each

other. Without once breaking the film’s

verisimilitude, Mungiu crafts a succession of gorgeous shots in which

characters are framed in ways that emphasize how distant they can be even when

standing right next to each other.

6) Zero Dark Thirty (Kathryn Bigelow, USA,

157 min.)

The fact that Kathryn Bigelow’s intense docudrama about

recent US foreign policy blunders has been attacked by both liberal and

conservative commentators suggests that it has struck a genuine nerve. Zero

Dark Thirty posits that the hunt for Osama Bin Laden was an extraordinary

but ultimately fruitless labor that wasted countless man hours, resources, and

lives to achieve something that did nothing to erase the pain brought about by

the events of 9/11 – and nothing to resolve the ongoing tensions between the

United States and the Middle East.

Socio-political commentary aside, this is simply the most intense

obsession-themed procedural since Zodiac

(2007), climaxing in an almost unbearably fraught depiction of the titular

mission.

B+ Special

7) Berberian Sound Studio (Peter

Strickland, UK, 92 min.)

A British sound mixer (Toby Jones) slowly loses his mind

while working on a sleazy Italian giallo in this slow-burning mind fuck. Director Peter Strickland (who previously

made 2009’s massively underappreciated Katalin

Varga) turns the horror genre inside out, keeping his camera away from the

apparently graphic footage of the film-within-a-film and on the sound crew as

they overdub screams or chop heads of lettuce to suggest stabs. This perspective, held for most of the

film, is so unique that the surreal Grand Guignol finale seems almost

disappointingly conventional by comparison.

8) Before Midnight (Richard Linklater,

USA, 109 min.)

Beginning with 1995’s Before

Sunrise, writer-director Richard Linklater, writer-star Ethan Hawke, and

writer-star Julie Delpy have been meeting once every nine years to tell the

ongoing story of a couple’s evolving relationship. Before

Midnight finds the duo married with kids, but struggling with buried

resentments that come to the surface during a trip to Greece. The filmmakers’ attempts to broaden the

series’ viewpoint by including other prominent speaking characters (such as the

ones found in an early dinner scene) don’t always pay off, but Hawke and

Delpy’s scenes together remain electrifyingly authentic, particularly during a

climactic argument that would be devastating even for viewers who don’t have

two decades of history with the characters.

Before Midnight isn’t as

perfect as its masterful predecessors, but it’s still an essential piece in the

greatest ongoing film series of our time.

9) All is Lost (J.C. Chandor, USA, 106

min.)

Gravity received a

great deal more press attention, but this starkly uncompromising film was the year’s most compelling tale of survival.

Robert Redford is the unnamed protagonist and sole cast member of All is Lost, and he spends the entire

film simply trying to survive after his ship begins sinking the middle of the

ocean. There is no backstory for

Redford’s character, nor are there any flashbacks or contrived plot points to

add unnecessary bells and whistles to his thoroughly engrossing struggle. Director J.C. Chandor shows such admirable

commitment to his no-dialogue, all-action aesthetic that the few benign

deviations from the film’s basic stylistic template (such as Alex Ebert’s mostly

non-intrusive ambient score) seem weirdly out of place.

10) Leviathan (Lucien Castaing-Taylor &

Verena Paravel, France/UK/USA, 87 min.)

Though ostensibly a documentary following the dangerous

exploits of a deep-sea fishing vessel, Leviathan

has less in common with Deadliest Catch

than it does with Gaspar Noe’s insane experimental feature Enter the Void (2010). The

camera seems completely untethered to the laws of physics as it swoops wildly

around the boat, sometimes dipping in and out of the water, sometimes capturing

passing seagulls from impossible vantage points, and sometimes simply observing

such bizarre sights as recently-caught skates being chopped in half by huge

machetes. The spell is periodically

broken by comparably generic static shots of the ship’s laborers struggling

through their day, but overall this is the most viscerally physical documentary

of recent memory.

11) Post Tenebras Lux (Carlos Reygadas,

Mexico/France/Germany/Netherlands, 115 min.)

Admittedly impenetrable yet undeniably stunning, Carlos

Reygadas’ fourth feature offered one of the best pure sensory experiences at

cinemas this year. Like Terrence

Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011), Post Tenebras Lux mixes an intensely

personal family story with metaphysical flights of fancy, and once again the

combination is as awkward as it is fascinating.

The film may ultimately be less than the sum of its parts, but many of

those individual elements – a CGI devil stalking around a live action house

during a storm; a bathhouse orgy that is somehow simultaneously sedate and

intense; an impromptu rendition of a Neil Young song that is all the more

haunting for being completely off-key; an abrupt self-decapitation - are as

sublime and as beautifully filmed as anything in recent memory. The lightning bolt edit between the first two

scenes single-handedly justifies the Best Director award that Reygadas received

for this film at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival.

12) This is Martin Bonner (Chad Hartigan,

USA, 83 min.)

Many popular works of art claim to be about redemption, but This is Martin Bonner is the rare film

that actually deals with that subject matter in an adult, realistic way. The story revolves around the titular social

worker’s (Paul Eenhoorn) attempts to help a repentant drunk driver (Richmond

Arquette) readjust to society after a twelve-year stint in prison. Bonner is dealing with his own crisis of

faith, seemingly related to some unspecified family trauma, and his own

distance from his loved ones mirrors the ex-con’s strained relationship with

the daughter (Sam Buchanan) who grew into a different person during his prison

stay. This material could’ve easily turned

into melodrama, but writer-director Chad Hartigan favors an understated, humane

approach that is perfectly complimented by the subtle, lived-in performances of

Eenhoorn and Arquette. This is Martin Bonner isn’t particularly

stylish – it could probably be just as easily enjoyed on a laptop screen as in

a cinema – but the lack of flash is appropriate to the story. The film isn’t small, it’s life sized.

13) House with a Turret (Eva Neymann,

Ukraine, 81 min.)

Set in a Soviet Union ravaged by World War II, Eva Neyman’s

depressive drama brings considerable weight to the story of a child (Dmitriy

Kobetskoy) who is forced to travel to his distant grandmother’s house alone

after his mother (Yekatarina Golubeva) dies of typhus mid-journey. The film’s perpetual grayness is mitigated

by its child’s-eye perspective, which provides some light surreal touches, as

well as some marvelously deadpan humor.

Though they are working very much in a familiar “European art film” aesthetic,

director Neyman and cinematographer Rimvydas Leipus are masters of creating haunting

black and white imagery, seeming less like imitators of Bela Tarr and Andrei

Tarkovsky than peers.

14) Laurence Anyways (Xavier Dolan, Canada,

168 min.)

Laurence Anyways

is the type of wildly impassioned project that has such a huge scope and takes

so many risks that it constantly seems on the verge of collapsing under the

weight of its ambitions. 24-year-old

writer-director Xavier Dolan (already on his third feature film) isn’t always

in full command of everything he’s trying to do, but it’s impossible not to

admire the stylistic chances he takes in telling the decade-spanning story of a

man (Melvil Poupaud) undergoing a gradual sex change, and the girlfriend

(Suzanne Clement) who struggles with adapting to his shifting sexual identity. Poupaud and Clement’s excellent performances

keep the story grounded even as Dolan indulges his most flamboyant artistic

whims, including a splendidly goofy sequence where the couple walks through a

storm of raining sweaters.

B Very

Good

15) Drug War (Johnnie To, China, 107 min.)

You’ve heard the story before: an undercover police officer (Sun Honglei)

coerces a questionably trustworthy drug dealer (Louis Koo) into betraying his

fellow cartel members as part of an undercover sting. But while it has the look of a standard Hong

Kong-style shoot-‘em-up, there’s nothing generic about Drug War, which finds prolific action specialist Johnnie To working

in peak form as he wrings every ounce of bizarre humor and sly social

commentary out of a stock plotline. The

epic shootout finale rivals Anchorman 2’s

climactic gang battle for over-the-top insanity, and suggests that To may be

the supreme action choreographer of his generation.

16) The World’s End (Edgar Wright, UK, 109

min.)

Most modern film comedies are lazily constructed, utilizing

a “point the camera at the improvisers” aesthetic that tends to create

scattershot results. In this context, a

smartly plotted, visually impressive film like The World’s End is a refreshing anomaly. Considering that they’d already previously

collaborated on Shaun of the Dead (2004)

and Hot Fuzz (2007), it’s clear that

stars Simon Pegg and Nick Frost enjoy working with director Edgar Wright, but

they thankfully produce results that feel like real cinema rather than just a

bunch of famous friends hanging out.

Pegg and Wright’s latest script follows a group of old friends as they

reunite to take a twelve-pub tour that they’d previously attempted as young

men. The only problem, aside from the

group’s exasperation with Pegg’s immature tour leader, is that their old home

town has been overrun by a mysterious cabal of pod people intent on both

“Starbucking” the formerly distinct area bars and turning the populace into

conformist drones. The script’s structure

is ingenious, in that it requires the characters to get increasingly drunk as

the film goes on, making their behavior funnier even as the dramatic stakes

increase.

17) Neighboring Sounds (Kleber Mendonca

Filho, Brazil, 133 min.)

Few films in recent memory have had as fully a developed

understanding of their setting as writer-director Kleber Mendonca Filho’s

feature film debut. Filho follows the

various residents of a Brazilian condo complex as they go about their daily

business, with an undercurrent of class resentment and paranoia giving their

interactions a tinge of subtle menace. A

rash of car robberies brings a mysterious security firm to the neighborhood,

but the film is less concerned with this thin strand of plot than with

beautifully capturing the ways that a neighbor’s blasting music or barking dog

can disrupt a person’s whole day. The

film’s refusal to follow narrative conventions is both a blessing and a

curse. On the one hand it always seems

as if anything can happen, but on the other hand it’s a bit frustrating that

the tensions never really come to a head, and only really result in a couple of

creepy nightmare sequences and a climactic revelation about one character’s

motives. Still, this is one of the most

promising debuts of the year, and I can’t wait to see what Filho does next.

18) The Rabbi’s Cat (Antoine Delesvaux

& Joann Sfar, France, 100 min.)

An Algerian cat gains the ability to speak after swallowing

the family parrot, setting the tone for this delightfully offbeat fantasy,

adapted from co-director Joann Sfar’s comic series. The film’s basic premise, which finds the cat

using its newfound ability to question its master’s religious beliefs, is

intriguing enough, but much of the film’s charm comes from the way that the

story branches off into a series of increasingly surreal digressions. Sfar’s rambling narrative is a double-edged

sword, as certain passages feel less fully realized than others, but the exotic

hand-drawn animation keeps the film transfixing.

19) Frances Ha (Noah Baumbach, USA, 85

min.)

One of the year’s nicest surprises, this tale of an aspiring

dancer (Greta Gerwig) struggling to find direction in her post-college life is

refreshingly free of knee-jerk miserablism, which is all the more remarkable

considering that it comes from discomfort specialist Noah Baumbach. The forced awkwardness of past Baumbach films

like Greenberg (2010) is replaced

here by a vibrant French New Wave-inspired aesthetic that matches the

caffeinated energy of its protagonist.

Where some of the director’s previous films seem perversely contrived to

be as confrontationally unlikeable as possible, Frances Ha realistically and fully captures the frustrations and

joys of its characters’ lives, not just the button-pushing parts.

20) 12 O’Clock Boys (Lotfy Nathan, USA, 75

min.)

Director Lotfy Nathan’s feature film debut is one of the

most beautifully filmed and edited documentaries in recent memory. With crisp slow-motion footage and an

energetic hip-hop soundtrack, Nathan captures the grace and recklessness of a

loose collective of Baltimoreans who perform insane dirt bike and ATV stunts on

crowded public streets. The film doesn’t

commit fully to the gorgeous impressionism of its extreme sports sequences –

and the brief asides about tragic accidents that some of the riders have been

involved in feel like token nods to social responsibility rather than serious

looks at the negative ramifications of the crew’s illegal brand of extreme

sports – but overall this is an exhilarating look at a singular

phenomenon.

21) Captain Phillips (Paul Greengrass, USA,

134 min.)

In 2009, freighter captain Richard Phillips (Tom Hanks) took

his ship on a mission through the dangerous Gulf of Aden, unaware that

desperate Somali pirate Abduwali Muse (Barkhad Abdi) was embarking on a speedy

skiff the same day. Captain Phillips is the intense true story of their battle of

wills, captured with an almost sickening sense of verisimilitude by ace action

director Paul Greengrass. The demands of

the action film framework ultimately overwhelm the filmmakers’ admirable

attempts to depict the pirates as fully fleshed-out people, despite the realistic

work of Abdi and the other Somali non-professionals in the cast. But Hanks’s

vanity-free lead performance is a powerful corrective to the type of inhumanly

stoic work that actors like Russell Crowe and Harrison Ford typically bring to

this type of role, climaxing in an overwhelmingly emotional breakdown that

feels like a reasonable response to the film’s events rather than fodder for an Oscar

clip.

22) Spring Breakers (Harmony Korine, USA,

94 min.)

The year’s most confounding film takes the trashy aesthetic

of MTV’s Spring Break coverage and haphazardly rearranges its tropes so that

they become alternately (and sometimes simultaneously) pornographic, comedic,

and horrific. At times Korine’s refusal

(or inability) to make a clear point with all of this provocation is

frustrating – especially when the film periodically leans toward cautionary

hysteria - but this is undeniably one of the most visually and aurally unique

films of the year. For some of the most

purely audacious filmmaking of recent memory, check out the inventive staging

of a restaurant stickup viewed entirely from the perspective of a creeping

getaway car, or the way that a sensationally violent montage is timed to flow

perfectly with a corny Britney Spears ballad.

James Franco’s deranged, semi-improvised performance as sleazy rapper

Alien sums the film’s odd tone up nicely: he’s somehow simultaneously funny,

seductive, menacing, and stupid.

23) Ain’t Them Bodies Saints (David Lowery,

USA, 96 min.)

The plot of David Lowery’s moody folk tale feels both

familiar and timeless: there’s an outlaw

(Casey Affleck), his faithful but distant lover (Rooney Mara), a kindly sheriff

(Ben Foster) who takes an interest in the outlaw’s lover, and a wise old man

(Keith Carradine) who knows that trouble is coming. But while the film’s aesthetic is derivative

of past classics like Badlands (1973)

and Thieves Like Us (1974), it’s hard

to complain when the old tropes are presented in such a beautiful package. Cinematographer Bradford Young’s shot

compositions are so rich and iconic that the poetic dialogue feels like a nice

bonus rather than a necessity.

24) Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley, Canada,

108 min.)

Sarah Polley’s recounting of her family tree has more

surprising plot twists and colorful characters than most of this year’s

fictional films. Too much of the latter

part of the film is devoted to generalizations about the untrustworthiness of

subjective memory, but Polley’s specific story is fascinating and gripping, and

makes for one of the most purely entertaining documentaries of recent memory.

25) No (Pablo Larrain, Chile, 118 min.)

In 1988, after fifteen years under military dictatorship,

the people of Chile were asked to vote on whether Augusto Pinochet should stay

in power for another eight years or whether there should be a democratic

election. No tells the true story of Pinochet’s opposition’s attempt to bring

the public to their side through a televised ad campaign lead by a slick

commercial veteran (Gael Garcia Bernal).

The film derives a lot of humor from simply re-airing a number of the

actual ads, which utilized cheesy soda commercial techniques to make political

activism seem fun and non-threatening.

But director Pablo Larrain, who also documented the repression of the

Pinochet era in his underrated and intense 2008 drama Tony Manero, never lets viewers forget the very real danger that

faced Chileans challenging the dictator’s authority, and his recreations of

government crackdowns feel queasily realistic.

26) American Hustle (David O. Russell, USA,

138 min.)

A real-life FBI investigation from the late ‘70s is turned

into a broad, affectionate Scorsese parody in David O. Russell’s entertaining

farce. Christian Bale, Amy Adams,

Bradley Cooper, Jeremy Renner, and Jennifer Lawrence are clearly having the

time of their lives in campy, scenery-chewing roles, and the fun is infectious.

27) Wolf Children (Mamoru Hosada, Japan,

117 min.)

Mamoru Hosada’s fantastical anime is a multi-layered coming

of age story about a woman tasked with raising two wolf/human hybrids on her

own after her shape-shifting lover is killed during a hunt. The animation is fairly generic (though

pretty), but the patient unfolding of the story is a nice alternative to the

manic pacing of most children’s films, and the ways that the narrative’s events

cause the children to either embrace or reject their lycanthropic heritage are

surprising and touching.

28) You’re Next (Adam Wingard, USA, 94

min.)

Adam Wingard’s taut thriller doesn’t reinvent the wheel when

it comes to the home invasion subgenre of horror films, but it does make every

other film of its type seem weaker by comparison. Anyone who’s seen The Strangers (2008) will instantly recognize the woods-surrounded house

that provides the film’s setting, and the masked killers who serve as the

antagonists. Less familiar is the

unusually well-constructed and witty script, which makes room for well-rounded

characters, clever twists, and (most refreshingly for the genre) villains who

are neither omniscient nor knife-proof.

29) Sightseers (Ben Wheatley, UK, 98 min.)

Ben Wheatley’s third feature lacks the daring tonal shifts

of his impressive previous efforts Down

Terrace (2009) and Kill List

(2011), but still features the careful attention to character and the stylistic

swagger that set the director apart from the pack of young horror

filmmakers. This horror-romantic comedy

hybrid follows a young couple (Alice Lowe and Steve Oram, both hilarious) on an

initially peaceful RV road trip that turns violent whenever they perceive that

other tourists are slighting them. The

concept (a romantic comedy where the couple is made up of complete sociopaths)

is fairly one-note, but it’s a note that Wheatley and his stars play exceptionally

well.

30) In the House (Francois Ozon, France,

105 min.)

Having not been impressed by Swimming Pool (2003), the only other film I’ve seen by

writer-director Francois Ozon, I had fairly low expectations for his latest

meta commentary on the nature of storytelling, revolving around a teacher

(Fabrice Luchini) who is increasingly sucked into the ongoing narrative of the

writing assignments of his most mysterious student (Vincent Schmitt). Fortunately the script (adapted from a play

by Juan Mayorga) is as witty as it is clever, and Luchini is hilarious as the

comfortably bourgeois teacher with frustrated artistic ambitions. For a film that is commenting on the tropes of erotic thrillers, the film never becomes particularly sexy or suspenseful,

but the light comic tone assures that it never suffers from the heavy handed

pretensions that brought down Swimming

Pool.

31) This Must Be the Place (Paolo

Sorrentino, Italy/France/Germany, 118 min.)

Unfairly dismissed by many at its Cannes premiere as a mere

piece of camp, Paolo Sorrentino’s road movie has a lot more going for it than

its goofy premise initially suggests.

Yes, this is the movie where Sean Penn stars as a reclusive Robert

Smith-style New Wave icon who travels across the United States to find the Nazi

war criminal that tormented his father during World War II, and that is an

undeniably unwieldy storyline that never fully comes together. But the individual scenes – encompassing

everything from an impromptu but highly competitive ping pong game to a

beautiful live performance of the Talking Heads classic that gives the film its

title - are all so inventively and passionately staged that the bigger picture

seems almost beside the point. Penn’s

impressive commitment to his larger than life character holds the film together

even as it consistently, and excitingly, dares to fly off the rails.

32) Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues (Adam McKay, USA,

119 min.)

A lot of the appeal of Will Ferrell and Adam McKay’s justly

beloved Anchorman (2004) has to do

with how shockingly bizarre its humor is.

Much of the surprise is inevitably lost in this belated sequel, which at

times feels like a pale imitation of the original despite still being wildly Dadaistic

by mainstream comedy standards. But

let’s not get too intellectual – this is still hands-down the most laugh-out

loud funny movie of the year, and even the scenes that feel like minor

variations on popular moments from the first film reliably feature at least one

hilarious joke.

33) 12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen, USA,

134 min.)

This slavery drama is somewhat awkwardly perched between its

tear-jerking, prestige film ambitions and director Steve McQueen’s cold,

distant aesthetic, but the true story of Solomon Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor) is

so undeniably powerful that the artistic flaws in its telling seem almost

beside the point. During the moments

when McQueen’s style does connect with the subject matter – as in a

dispassionate tracking shot through a slave auction, and a brutally extended

quasi-lynching – the film becomes truly overwhelming.

34) Not Fade Away (David Chase, USA, 112

min.)

The radical social changes of the ‘60s are such well-trod

dramatic territory that even a talent as singular as Sopranos creator David Chase can’t make it feel entirely

fresh. Still, the perspective of Not Fade Away, which is based around

events from Chase’s youth, is specific enough to make up for the familiarity of

tropes like the working-class father (James Gandolfini) who doesn’t understand

his son’s (John Magano) new long haircut.

Chase’s elliptical narrative style and careful attention to period

detail prevent the film from feeling like a costume party, as so many other

movies set during the same era do, and nearly every scene is inventively staged

and edited even when its content seems like it should feel rote.

35) The Place Beyond the Pines (Derek

Cianfrance, USA, 140 min.)

Writer-director Derek Cianfrance’s crime saga is so

ambitious that each of its three acts is practically its own distinct

film. The structure is fascinating but

flawed, as each segment is a little less interesting than the last. Ryan Gosling stars in the first act as a

motorcycle stuntman who turns to bank robbery, a scenario that allows for both

atmospheric romantic brooding and a visceral climactic car chase. The second segment follows a cop (Bradley

Cooper in a rare understated performance) seeking to bring down corruption in

his precinct, a scenario that is intriguingly complicated by an unjust shooting

that he is involved in. The sons of the

cop and the bank robber become the protagonists in the third and most

problematic act, which labors too hard to create drama out of unconvincing

generational connections. While there is

the sense overall that the film’s tricky structure might have worked better in

the form of a novel or a TV series, Cianfrance’s sheer ambition is an

achievement in and of itself, and there was nothing else quite like this movie

this year.

36) Iron Man 3 (Shane Black, USA, 130 min.)

After a bland-but-efficient first installment and a

disastrous mess of a second film, there was little reason to expect the third

film in the hugely popular Iron Man

series to be as much fun as it turned out to be. Following an explosive attack on his

ocean-side mansion, Tony Starks (Robert Downey Jr.) is forced to spend a large

chunk of the film without his superhero suit, and the shift in focus from

generic action pyrotechnics to basic human storytelling simultaneously increases

the dramatic stakes and provides more opportunities to enjoy the lead

character’s acerbic wit. It helps that

co-writer/director Shane Black has taken the reigns from Jon Favreau, injecting

some actual personality into the Marvel Films house style. When the action does come, as in a thrilling

mid-air rescue sequence, it illuminates Starks’ character arc as well as

providing visceral excitement. In all,

this is the best of the Marvel films to date, superior even to The Avengers (2012).

37) The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (Francis Lawrence, USA, 146

min.)

Who would’ve guessed, after last year’s awkwardly visualized

first installment, that the Hunger Games

series’ second chapter would be one of the most genuinely exciting action

blockbusters of recent memory? With the

introduction of a mysterious government official (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and a

new competition involving a large number of past Hunger Games tournament

winners, the narrative is more knotty than ever, but the film jumps directly

into action with a welcome minimum of audience handholding. Though the allegory is still a bit of a mess,

the island setting is much more richly cinematic than the first film’s dull CGI

wasteland, and director Francis Lawrence gives the action sequences a genuine

sense of suspense.

38) The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (Sophie

Fiennes, UK/Ireland, 136 min.)

39) Enzo Avitabile Music Life (Jonathan

Demme, Italy, 80 min.)

B- Good

but flawed or insubstantial

40) Holy Motors (Leos Carax, France, 115

min.)

Leos Carax’s first feature film since 1999’s Pola X boasts enough ideas to suggest

that he’d been working on it for the entire interim. Unfortunately not all of the concepts are

equally well developed, and the hit-or-miss nature of the entire enterprise

makes Holy Motors feel like the art

film equivalent of a sketch comedy movie.

The connecting structure of the film, which finds an enigmatic man

(Denis Lavant) attending a series of different appointments in which he

transforms into different characters, is intriguing, but only a few of his

roles live up to their promise. For

example, a brief sequence in which the protagonist appears as an elderly beggar

seems to exist solely to provide a stark contrast to the following, much more

interesting appointment in which he performs a variety of acrobatic stunts

while wearing a motion-capture suit.

Though the overall results are a bit scattershot, the film does find

some consistency in its gorgeous cinematography and in Lavant’s marvelously

physical performance(s).

41) To the Wonder (Terrence Malick, USA,

112 min.)

With its mix of working-class family drama and vague New Age

spirituality, To the Wonder feels

like an epilogue to Terrence Malick’s previous film, The Tree of Life (2011). Individual

moments demonstrate Malick’s continuing stylistic majesty – a lengthy montage

in which Ben Affleck’s protagonist has a dalliance with Rachel McAdams’

character is as bewitching a combination of sound and vision as the cinema has

ever produced – but after a while the many scenes of people frolicking

idyllically begin to resemble perfume commercials, and the film’s religious

content (represented by Javier Bardem’s conflicted priest) seems imported from

another movie. Any film with this amount

of sublime Emmanuel Lubezski widescreen shot compositions is ultimately a

must-see, but here’s hoping that Malick shifts his focus a bit in his next

project.

42) Closed Curtain (Jafar Panahi &

Kamboziya Partovi, Iran, 106 min.)

In 2010, the great Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi was

sentenced to a 20-year ban on filmmaking due to the subversive political

content of his films. Closed Curtain is the second movie that

Panahi has made in secret and had smuggled out of the country since then. It begins as a compelling allegory for

Panahi’s current life situation, with a writer (played by co-director Kamboziya

Partovi) boarding himself up in his house so that the authorities won’t become

aware of his dog’s existence (the animals are considered unclean under Islamic

rule). The sudden arrival of two

mysterious people seeking shelter from the law brings exactly the type of

attention that the writer was hoping to avoid.

This opening half of the film is exciting and tense, featuring brilliant

use of offscreen sound as unseen assailants storm around outside the writer’s

house. Unfortunately, when Panahi

himself takes over as the protagonist in the second half of the film (as if the

allegory wasn’t already clear enough), the film turns into a clumsily symbolic

retread of material from 2011’s far superior This is Not a Film. Panahi’s

focus on his current predicament is understandable, but hopefully he’ll find a

way to make a film about any other subject next time rather than continuing to

cover the same ground.

43) Room 237 (Rodney Ascher, USA, 102 min.)

Though it’s hardly Stanley Kubrick’s most cryptic film, The Shining (1980) has inspired an

enormous amount of fan speculation about its subtext. Several of those theories are explored in

this entertaining documentary, which finds a number of unseen narrators

explaining their theses while illustrative clips from the film play. Frustratingly, director Rodney Ascher doesn’t

really challenge any of the narrators’ ideas, giving equal weight to

illuminating discussion of Kubrick’s subtle disorientation techniques and

far-fetched conspiracy theories that insist that the film was Kubrick’s elaborate apology for faking

the U.S. moon landing. Still, the

documentary is never less than entertaining, and its most trippy section (in

which one of the narrators simultaneously projects the film forwards and

backwards, creating weird symmetries) is mesmerizing.

44) Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel & Ethan

Coen, USA, 105 min.)

Some of the Coen Brothers’ films suffer from a scattered

attention span, but Inside Llweyn Davis

is a little too focused for its own good.

The film never leaves the side of the titular folk singer (Oscar Isaac),

who can’t seem to catch a break in his personal or professional life since the

death of his former musical partner. The

Coens accurately capture the feeling of being stuck in an endless loop of

frustration and self-hatred, but since Davis pointedly ends up in the same

place that he started the film in, there is no sense of dramatic

progression. Gorgeous cinematography

from Bruno Delbonnel and a meticulous attention to period detail keep the film

modestly engaging, but it only really jumps to life with an extended cameo by

John Goodman as an ornery jazz musician, and during a recording of goofy

novelty song “Please Mr. Kennedy,” both of which seem imported from a more

lively Coens film.

45) Only God Forgives (Nicolas Winding

Refn, France/Thailand/USA, 89 min.)

Only God Forgives

is action specialist Nicolas Winding Refn’s equivalent to Gasper Noe’s Enter the Void (2010), in that it pushes

all the best and worst aspects of its director’s aesthetic to their logical

conclusion, resulting in a film that is equally masterful and idiotic at all

times. To find such consistently bold

and expressive use of color you’d have to look back to Michelangelo Antonioni’s

Red Desert (1964), or perhaps the

Powell & Pressburger masterpieces of the ‘40s. To find such consistently repellent subject matter

and such moronic Oedipal themes you can refer to the lesser films of Oliver

Stone. In any case, this is not a boring film, and you have to

admire Refn’s willingness to push every aspect of it to its ultimate extreme,

even when it (frequently) makes everything onscreen seem completely

ludicrous. On a story and thematic level

this may be the dumbest movie of the year, but as a pure sensory experience it

has few rivals.

46) The Counselor (Ridley Scott, USA, 117

min.)

The critical whiplash surrounding The Counselor (with a handful of commenters racing to its defense

after some early reviews declared it to be an unmitigated disaster) is in some

ways as interesting as the film itself.

Really the film, taken from novelist Cormac McCarthy’s first original

screenplay, is neither great nor terrible, but its stubborn refusal to satisfy crime narrative expectations is perversely fun, as if someone had somehow made a film entirely out of

variations on the grave anti-climax of No

Country for Old Men (2007). The

skeletal plot concerns Michael Fassbender’s lawyer, who immediately gets in

over his head when he agrees to participate in some unspecified corruption

involving a violent drug cartel, but the movie really exists so that a cast of

superstars can deliver McCarthy’s rambling philosophical monologues. Some of the performers handle the script’s

mannered non sequiturs better than others – Brad Pitt is hilarious as a

world-weary consultant who is constantly exasperated by Fassbender’s

gullibility, while Cameron Diaz is fatally miscast as an icy femme fatale – but

the film is certainly never boring, and its weirdness forces Ridley Scott out

of the middlebrow funk that he’s been in for over a decade. At any rate, The Counselor is no more pretentious, and far more entertaining,

than Prometheus (2012).

47) The Comedy (Rick Alverson, USA, 94

min.)

Tim Heidecker proves that he can believably play a serious

role in this uncomfortably intimate character study, which, despite its title,

is a bleak look at the limitations of ironic detachment. At times the film strains credulity in

order to pile on button-pushing misery – a scene where the protagonist blankly

stares on as a sexual conquest has a seizure doesn’t seem enough like

recognizable human behavior to be as disturbing as it’s presumably meant to be

– but Heidecker’s uncompromisingly brutal portrayal of hostile misanthropy

makes this a must-see.

48) Fruitvale Station (Ryan Coogler, USA,

85 min.)

The real life police shooting of Oscar Grant III, which was

captured on a cellphone camera, is unquestionably a tragedy, which makes

writer-director Ryan Coogler’s attempts to valorize his protagonist by turning

him into a hero all the more unnecessary and manipulative. In imagining the hours leading up to the

shooting, Coogler depicts Grant (Michael B. Jordan) throwing away the drugs he

was going to sell and cradling a dog killed by a hit-and-run driver. Fortunately Jordan, a veteran of The Wire, resists the script’s attempts

to turn Grant into a simplistic hero and brings a mixture of volatility and

vulnerability to the role, turning a potentially cloying film into a frequently

powerful experience.

49) Nebraska (Alexander Payne, USA, 115

min.)

In a Midwest farm country so barren that it could only be

presented in black and white, an elderly drunk (Bruce Dern) attempts to travel

by foot to Lincoln to claim a publisher’s clearinghouse “prize.” Half senile and bruised by the failures of

his past, the old man has enough sentiment left to allow his son (Will Forte)

to join him on his misguided quest. The

late-blooming father and son bonding session might have proven cloying in the

wrong hands, but Dern and Forte (in a rare semi-dramatic role) underplay the

relationship effectively, never going for easy tear-jerking moments. Whenever the film threatens to get too

maudlin or crowd-pleasing, the exceptional cast (which also includes June

Squibb, Bob Odenkirk, and Stacy Keach) gets things back on track.

50) Something in the Air (Olivier Assayas,

France, 122 min.)

Though this early-‘70s period piece is reportedly based on

events from director Olivier Assayas’ youth, its narrative suffers from the

same stasis as his previous film, Carlos

(2010); it is clear, literally from the first shot, that Assayas thinks that

his student activist protagonists are poseurs.

Assayas may be in a rut as a storyteller, but thankfully he remains one

of the most expressive and energetic stylists alive. The fetishistic attention to specific

“revolutionary” tchotchkes and fashions of the ‘70s keeps the film engaging

even as Assayas seems to insist that we not invest in his characters.

51) Blancanieves (Pablo Berger, Spain, 104

min.)

Pablo Berger’s silent, bullfighting-themed variation on Snow

White won Best Film at the most recent Goya Awards (Spain’s equivalent to the

Oscars), but, like The Artist (2011),

it never really transcends its gimmicky origins as an homage to silent

cinema. The gorgeous cinematography and

scenery are enough to keep the film largely diverting.

52) From Up on Poppy Hill (Goro Miyazaki,

Japan, 91 min.)

53) Pacific Rim (Guillermo del Toro, USA,

131 min.)

54) Star Trek Into Darkness (JJ Abrams,

USA, 132 min.)

C+ Decent

55) The Grandmaster (Wong Kar-wai, Hong

Kong, 108 min.)

Wong Kar-wai may be the most passionately stylish director

working in cinema today, but you wouldn’t know it from the Weinstein Brothers’

edit of Wong’s latest. The awkward

pacing and ridiculously truncated story make the severe compromises obvious even

to those of us who weren’t lucky enough to see Wong’s international edit (which

is 22 minutes longer, features far fewer explanatory intertitles, and shows

many of the scenes in a different order).

Still, the Weinsteins’ butcher job can’t entirely disguise Wong’s

artistry. This is the rare martial arts

film that focuses on the formal beauty of its fighters rather than the carnage,

and the way that Wong playfully zooms in on and slows down the thrusting fists

and flying feet is both unique and poetic.

Given his track record, Wong presumably brought a similar elegance to

this film’s structure, but U.S. audiences may never know for sure.

56) Gravity (Alfonso Cuaron, USA, 91 min.)

Gravity was being hailed

as a modern classic by many critics before it was even released, but it

ultimately comes across more as a glorified tech demo than a compelling

movie. The film is undeniably a major

special effects achievement, featuring the most sophisticated use of digital 3D

to date, with ace cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki working seamlessly with a

large computer graphics team to create a truly convincing depiction of

space. If only the distracting

narrative, built around a cheesy backstory for an astronaut played by Sandra

Bullock (in a typically muggy performance), didn’t get in the way of the

potentially gripping stranded in space scenario.

57) This is the End (Evan Goldberg &

Seth Rogen, USA, 107 min.)

Evan Goldberg and Seth Rogen’s apocalyptic Hollywood satire

is endearingly personal and quirky for a mainstream comedy, but it pales in

comparison to the similarly themed, and much more tightly constructed, The World’s End. The loose, improvisational vibe occasionally

pays real dividends, as in a hilarious ejaculate-based argument between James

Franco and Danny McBride (playing exaggerated versions of themselves), and the

supernatural scenario gives the filmmakers license to get into some fairly

unusual territory. But Goldberg and

Rogen, stepping behind the camera for the first time, display very little

visual talent, and overindulge their superstar cast, making this feel like a

film that was more fun to make than it is to watch.

58) Much Ado About Nothing (Joss Whedon,

USA, 109 min.)

Joss Whedon & co’s modern-dress adaptation of one of

Shakespeare’s most beloved comedies is almost literally a home movie, filmed at

Whedon’s household during a hiatus from filming The Avengers (2012). It’s

clear that the Whedon regulars are having fun, and Alexis Denisof and Amy Acker

are charming as the central couple, but there is really no compelling reason

for this umpteenth version of the story to exist. It feels more like an extended DVD bonus than

a theatrical feature.

59) Man of Steel (Zack Snyder, USA, 143

min.)

Despite all of the (largely deserved) flak that Zack Snyder

receives for brazenly appealing to the lowest common denominator of mainstream

nerd fantasies, he has an undeniable talent for creating instantly iconic shot

compositions, a skill that serves him well in telling a Superman story. But while Man

of Steel is one of the more visually spectacular action films of the year,

it still suffers from the bloated running time and overly convoluted mythology

building endemic to so much modern blockbuster filmmaking.

60) The Hobbit:

The Desolation of Smaug (Peter Jackson, New Zealand, 161 min.)

61) The Loneliest Planet (Julia Loktev,

USA, 113 min.)

62) A Band Called Death (Mark Christopher

Covino & Jeff Howlett, USA, 96 min.)

63) The Crash Reel (Lucy Walker, USA, 108

min.)

64) War Witch (Kim Nguyen, Canada, 90 min.)

C Mediocre

65) Upstream Color (Shane Carruth, USA, 96

min.)

The quality of surreal, dreamlike films is even more

subjective than the quality of most art; you either get hypnotized by them or

you don’t. Having been mightily

impressed by Shane Carruth’s previous film, Primer

(2004), I was prepared to follow him pretty far down the rabbit hole on Upstream Color, but I have to admit that

I couldn’t really get on the film’s inscrutable wavelength. This could be because of my preference for

the long-take, creeping dread of something like Mulholland Drive (2001) over the Nicolas Roeg-style non-stop

fragmented editing Carruth employs here, or it could be because the obscure

plot (having something to do with a mad scientist using a virus that infects

the memories of its protagonists) seems less like a compelling mystery than a

somewhat clichéd sci-fi story told from an odd angle. Carruth certainly deserves credit for his

industriousness – he wrote, directed, scored, co-edited, starred in, and even

helped operate the camera on this film, and made a slick looking product on a

shoestring budget. I just wish that he

had used his undeniable talent on something more compelling than footage of pigs

milling around, or his lead characters arguing about which of their memories

are real. Aside from one mesmerizing

scene in which the wormlike virus makes its way through the female lead’s (Amy

Seimetz) body, the film is largely tedious.

66) The Lords of Salem (Rob Zombie, USA,

101 min.)

Rob Zombie is perhaps the most talented director working

today to have never made a wholly successful film, and he continues to get in

his own way with this occult-themed head-trip.

Sherri Moon Zombie stars as a disc jockey whose mind begins to unravel

after she receives a mysterious recording containing subliminal satanic

messages. The film becomes increasingly

surreal as the heroine’s mind continues to unravel, and Zombie (along with

cinematographer Brandon Trost) gets plenty of chances to display his undeniable

skill for creating fucked-up imagery.

The trouble is that Zombie can’t seem to distinguish his good ideas from

his dreadful ones. In the film’s insane

Grand Guignol climax a genuinely menacing

shot of a slowly approaching satanic processing is followed by an unintentionally hilarious shot of a Marilyn Manson type

dry-humping the protagonist while wagging his tongue at the camera. The contrast between the serious horror of the first shot and the unintentional humor of its follow-up sadly sums up Zombie's career as a filmmaker to date.

67) Gangster Squad (Ruben Fleischer, USA,

113 min.)

68) Texas Chainsaw 3D (John Luessenhop,

USA, 92 min.)

69) Evil Dead (Fede Alvarez, USA, 91 min.)

70) Free the Mind (Phie Ambo,

Denmark/Finland, 80 min.)

71) Bound by Flesh (Leslie Zemeckis, USA,

95 min.)

C- Below

Average

72) Reality (Matteo Garrone, Italy, 116

min.)

I was not as blown away by Matteo Garrone’s breakthrough

film Gomorrah (2008) as most critics

were, so I was looking forward to this goofy farce simply as a radical change

of pace. But while Gomorrah may have been too didactic for its own good, its

single-mindedness at least gave it a certain forceful vitality that is completely

missing from this slackly paced follow-up.

A fishmonger (Aniello Arena) becomes obsessed with appearing on a

popular reality show, to the point that he ultimately gives away all of his

possessions. Despite the too-obvious

satirical target of reality TV, this story might have worked had Garrone

consistently amped up the lunacy to match his protagonist’s story arc, but

stylistically the film works backwards, beginning with a party scene that

suggests Fellini-esque carnival extravagance and then slowly settling into a

dully respectable tonal register that just doesn’t work for comedy.

73) Hara-Kiri:

Death of a Samurai (Takashi Miike, Japan, 126 min.)

Takashi Miike’s samurai remake copies many of the elements

of Masaki Kobayashi’s 1962 masterpiece Harakiri

verbatim, but misses the touches that make the original so distinctive. Ebizo Ichikawa’s wooden lead performance is

no match for the grim reaper presence of Tatsuya Nakadai in the original film,

and the generic string section score of Ryuichi Sakamoto is unmemorable

compared to the original’s strikingly abrasive use of koto and woodblock. Worst of all, the remake spends nearly half

of its running time on an extended flashback that completely kills the story’s

momentum, whereas the original ingeniously parceled out the backstory to build

tension in the main plot.

D+ Bad

74) Bullet to the Head (Walter Hill, USA,

92 min.)

D Awful

75) The Rambler (Calvin Lee Reeder, USA, 97

min.)