August: Osage County (John Wells, USA, 2013, 121

min.)

Viewed Theatrically First Viewing

The key to successfully adapting playwright Tracy Letts’

work to film is full commitment to the sleaziness of the material, as

demonstrated in William Friedkin’s memorably lurid adaptations of Bug (2006) and Killer Joe (2011). August:

Osage County certainly leaves plenty of room for over-the-top

melodrama, as the material touches on everything from parental abuse to incest

to underage sex, but the filmmakers were determined to turn this trashy

material into an award-winning prestige film, and the competing agendas of the

script and the direction produce a confused product. This tale of the world’s most dysfunctional

family reunion is intermittently enjoyable as a showcase for its impressive

ensemble cast, though the supporting players are too often steamrolled by Meryl

Streep’s over-the-top mugging as the family’s pill-popping matriarch. C+

Blue Jasmine

(Woody Allen, USA, 2013, 98 min.)

Viewed on Itunes First Viewing

Woody Allen lost his skill for capturing realistic human

behavior decades ago, so he’s hardly the ideal writer-director for a character

study revolving around class distinctions.

It’s no surprise that Allen seems to have no idea how modern working-class

people behave, but his treatment of the wealthy characters here is almost equally

broad and stereotypical. While the

film’s insight into current social issues is limited, the script does have a

surprisingly elegant and smartly employed flashback structure, and the

fantastic cast manages to make most of their characters vivid even if they

aren’t entirely believable. Cate

Blanchett is fantastic as a woman struggling to maintain her socialite

lifestyle after her Bernie Madoff-like husband (Alec Baldwin) is arrested. B-

City of Women (Federico

Fellini, Italy, 1980, 140 min.)

Viewed on Itunes Second Viewing

Federico Fellini was one of the cinema’s great sensualists,

to the point that it’s honestly kind of a shame that he didn’t devote the

latter half of his career to making pornography. Like most of the director’s post-8 ½ (1963) films, City of Women is a loosely-scripted, visually spectacular, and

extremely overlong collection of dreams revolving around a theme, which in this

case is male chauvinism. While the film

makes some half-hearted attempts to satirize its lothario protagonist’s

(Marcello Mastroianni) outdated attitudes toward the opposite sex, it is

ultimately much more convincing (and frankly far more enjoyable) during the

moments when Fellini indulges in outrageous setpieces that allow him to flaunt

his most absurd masturbatory fantasies.

A climactic sequence in which Mastroianni is waited on by adoring female

servants while ogling the cartoonishly voluptuous body of Donatella Damiani

tops even the famous harem sequence of 8

½ as a combination of goofy humor and genuine sexiness. But while a few of the individual scenes impress,

the film as a whole is a tedious slog. C+

Dallas Buyers Club (Jean-Marc Vallee, USA, 2013, 117 min.)

Viewed on DVD First Viewing

The details of this true story are so fascinating and

complex that it’s all the more a shame that the broad outlines feel engineered

for maximum viewer uplift. Ron Woodruff

(played here by Matthew McConaughey, in a fantastic performance) was given

thirty days to live after receiving an AIDS diagnosis in the mid-80s, but

managed to live another seven years thanks to imported medicines not approved

by the FDA. With the help of an

HIV-positive transgender woman (Jared Leto) and a sympathetic doctor (Jennifer

Garner, in a thankless role), Woodruff sets up a “buyers club” where he

distributes the effective but illegal drugs to other AIDS victims. This underground economy and its political

ramifications are compelling, but the focus of the film is largely on

Woodruff’s predictable (and unconvincingly speedy) softening of his initially

conservative attitudes. C+

Days of Being Wild

(Wong Kar-Wai, Hong Kong, 1990, 94 min.)

Viewed on Netflix Second Viewing

Wong Kar-wai was still finding his style in 1990, and his

second feature is limited by isolated moments of generic melodrama and one

particularly out of place burst of gangster movie violence. The film as a whole doesn’t hold up in

comparison to In the Mood for Love

(2000), a later Wong film that was also set in the 1960s and similarly

concerned with frustrated romanticism, but the many moments that do work feel

remarkably assured and inventive for an early work. Many of Wong’s stylistic trademarks are here,

and while they aren’t as fully developed as they would be even by the time of Chungking Express (1994) there is still

a welcome sense of discovery and playfulness to the way that they are employed

here. Cinematographer Christopher Doyle

gives the film a distinctive green color palette, and makes the sweatiness of

the film’s summer setting palpable, allowing the viewer to identify with the

anger of the protagonist (Leslie Cheung).

The film is mainly concerned with

Cheung’s simultaneous romantic flings with a shop girl (Maggie Cheung) and a

dancer (Carina Lau), but it’s the strange asides (poetic dialogue in the

voiceover narrations, actions being glimpsed from odd angles) that linger in

the mind. Indeed the most mesmerizing

moment might actually be the baffling final scene, which simply watches a

previously unseen character (Tony Leung) as he silently gets ready for a night

on the town. The scene was ostensibly

meant to lead into a sequel that was never produced, but in hindsight it feels oddly

like a preview of great things to come, and the announcement that the greatest

director of his generation has arrived. B

eXistenZ (David

Cronenberg, Canada, 1999, 97 min.)

Viewed on Netflix First Viewing

David Cronenberg returns to Videodrome (1983) territory with this surreal nightmare, except

this time he’s substituted virtual reality for television and VHS. Security guard Jude Law is sucked into a

complicated game run by superstar designer Jennifer Jason Leigh. Unfortunately Cronenberg is in too much of a hurry

to let his freak flag fly, and he rushes quickly past setting up the premise to

get to the outrageous stuff: bone guns

that fire teeth, disgusting meals made of half-dead mutant animals, “game pods”

that look like umbilical cords. It gets

silly pretty quickly, especially since Cronenberg seems to have a limited

understanding of what makes video games appealing. It’s simply hard to imagine anyone enjoying

the game within the movie, or even to discern what its goal might be. C

The Grand Budapest

Hotel (Wes Anderson, USA, 2014, 100 min.)

Viewed Theatrically First Viewing

For a film that was obviously meticulously storyboarded and

choreographed, The Grand Budapest Hotel

is remarkably light on its feet, and I doubt that a funnier movie will be

released this year. Wes Anderson is

often criticized for repeating himself, but here his familiar diorama aesthetic

has been sharpened and refined to such a perfect sheen that viewers may feel

like applauding at regular intervals.

The plot is too deliriously complicated to sum up in a quick paragraph,

but suffice to say it follows the adventures of a classy hotel concierge (Ralph

Fiennes, never better) and his favorite lobby boy (impressive newcomer Tony

Revolori) in 1930s Europe. The film

breathlessly incorporates elements of adventure films, spy capers, heist films,

suspense, and even the prison break genre, and handles it all with a humor and

grace that make a good argument for Anderson as the sharpest filmmaker of his

generation. At many times the film

favorably recalls such classics of cinematic opulence as Ernst Lubitsch’s Heaven Can Wait (1943) and Powell and

Pressburger’s The Life and Death of

Colonel Blimp (1943), but the sense of humor unmistakably belongs to

Anderson himself. The film may not have

the emotional resonance of Rushmore

(1998) or The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

– the thinly developed romance that the lobby boy has with Saoirse Ronan’s

character feels mostly like a plot device, for example – but the epilogue

alluding to the encroaching influence of fascism has a certain melancholic

power. The outstanding supporting cast,

a combination of Anderson regulars like Adrien Brody, Owen Wilson, Jeff Goldblum,

Bill Murray, Edward Norton, and Willem Dafoe, and ringers like Mathieu Amalric,

F. Murray Abraham, Jude Law, and Tom Wilkinson is exceptional, and the film is

simply a delight. A-

Her (Spike Jonze,

USA, 2013, 126 min.)

Viewed Theatrically First Viewing

In Spike Jonze’s fourth feature film, Joaquin Phoenix plays

a man who develops an intimate relationship with a Siri-like operating system

(voiced by Scarlett Johansson). Jonze

wrote the script himself this time out, and while it’s tempting to imagine the

more biting and conceptually bold film that his frequent collaborator Charlie

Kaufmann might have made from the same premise, there are clear advantages to

Jonze’s gentler approach. For example, a

heartbreaking scene where the operating system attempts to make physical

contact with Phoenix through a sex surrogate might have stood out less and been

less effective in a more satirical film.

Phoenix’s raw nerve performance is very affecting, and Johansson finds

the perfect balance between warm, human sexiness and cold computerized precision. The film is also subtly visually impressive,

with Jonze making smart use of contemporary Shanghai location shooting to

create a futuristic city on a budget. B

High Anxiety (Mel

Brooks, USA, 1977, 94 min.)

Viewed on Blu-Ray First Viewing

The cinema of Alfred Hitchcock gets the full Mel Brooks

treatment in this silly spoof.

Unfortunately Brooks doesn’t quite nail the tricky mixture of reverent

homage and crude parody that made Young

Frankenstein (1974) so enjoyable.

The earlier film took great pains to capture the smallest stylistic

details of its target, but even major aspects of High Anxiety, such as the casting of schlubby Brooks as the

protagonist, don’t feel true to Hitchcock.

C

History of the World, Part I (Mel Brooks, USA, 1981, 92 min.)

Viewed on Blu-Ray Second Viewing

Though History of the

World, Part I doesn’t have the legacy of The Producers (1967), Blazing

Saddles (1974) or Young Frankenstein,

it is Mel Brooks’ most ambitious and interesting film. The sketch film structure, which purports to

tell the history of man from caveman times through the French Revolution, is an

ideal fit for Brooks’ vaudevillian sensibilities, and the variety show format

largely makes up for the hit-and-miss nature of the jokes. The bits that do work are among Brooks’

finest, with a hilariously tasteless Spanish Inquisition musical number

standing out as a particular highlight. B

Knightriders

(George Romero, USA, 1981, 146 min.)

Viewed on YouTube First Viewing

George Romero took a break from the horror genre with this

bizarre drama about a travelling Renaissance Fair where the knights joust on

motorcycles rather than horseback. The

writer-director evidently intended the ragtag troupe’s unusual act to be a

stand-in for his own independently made projects – which makes this in some

ways the Romero equivalent of John Cassavetes’ Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976) – but the allegory is a little

too goofy for its own good. Ultimately

the film is almost excessively personal, sacrificing any sense of shape or

pacing in favor of a drifting succession of scenes in which the Knightriders

have run-ins with local authorities, squabble over the prospect of being

sponsored by a slick agency that wants to control their image, and struggle to

maintain their artistic purity in front of drunken audiences. The film is a mess, but its shagginess

sometimes works to its advantage, with the rambling non-narrative allowing

plenty of room for slice of life scenes that make the group’s camaraderie feel

convincing and touching. Ed Harris (in

his first lead role) is almost frighteningly committed in his role as the

Renaissance Fair’s stern King, and legendary makeup artist Tom Savini has a

surprisingly strong acting turn as the more pragmatic challenger to the

throne. B-

Rancho Notorious

(Fritz Lang, USA, 1952, 89 min.)

Viewed on Watch TCM First Viewing

Fritz Lang’s authorial stamp is scarcely present in this

kitschy low-budget western, set in an outlaw hideout run by Marlene

Dietrich. The peace is broken when

Arthur Kennedy shows up looking for the man who murdered his fiancée. Though the recurring theme song promises a

tale of “hate, murder and revenge” those feelings aren’t remotely as vivid here

as they are in the films where Lang was more than just a hired hand. C+

Red Hook Summer (Spike

Lee, USA, 2012, 121 min.)

Viewed on Netflix First

Viewing

Seemingly created for the sole purpose of challenging She Hate Me (2004) for the title of

“least focused Spike Lee joint,” this wild jumble of half-formed ideas is

another of the sometimes-great director’s features to suggest that he should

avoid writing original screenplays and instead focus on making high-quality

documentaries. Though ostensibly the story of a young, comfortably

middle-class boy from Atlanta (Jules Brown) spending a summer in Brooklyn with

his poor, fiery preacher grandfather (Clarke Peters), the film is really an

outlet for Lee to comment randomly on religion, class, race, gentrification,

technology, single parenthood, the U.S. occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq, Do the Right Thing (1989), hip hop, gang

life, generational gaps, the stock market, the New York Knicks, and seemingly

anything else that came to his mind while he and James McBride were working on

the screenplay. The film’s crazy

ambition to fit it all in is sometimes invigorating, but it quickly becomes

clear that Lee hasn’t thought through what he wants to say about any of these

topics. It doesn’t help that the

director chose to shoot the film in a deliberately amateurish way, his ugly

digital footage being overlaid with non-stop blaring music. Peters, a veteran of The Wire and Treme,

sometimes manages to corral the film’s energy with the sheer magnitude of his

volcanic performance, but he outclasses the rest of the cast to a distracting

degree. C

RoboCop (Jose

Pedihla, USA, 2014, 117 min.)

Viewed Theatrically First Viewing

Jose Pedihla’s remake of Paul Verhoeven’s popular 1987

action-satire hybrid makes some promising early attempts at contemporary social

commentary, but ultimately focuses so much of its energy on being a dark origin

story that it winds up feeling like just another generic action franchise

reboot. The opening scene makes some

enticing allusions to drone warfare, the U.S. occupations of Afghanistan and

Iraq, and Fox News, but the script never really follows through with these

inquiries, and instead spends an interminable amount of time simply watching

the hero (Joel Kinnaman) adjust to his new cyborg body. By the time the film has reached its

protracted “get to the helipad” shootout finale, it feels like we could be

watching literally any action movie of the last three decades. D

Rust and Bone

(Jacques Audiard, France, 2012, 120 min.)

Viewed on DVD First Viewing

A street fighter (Matthias Schoenaerts) develops a sexual

relationship with a paraplegic killer whale trainer (Marion Cotillard) in this

macho (and muddled) drama from Jacques Audiard, director of the vastly superior

A Prophet (2010). The plot promises action, melodrama, and

general cult movie craziness, but Audiard inexplicably stages the film as a

muted, “realistic” character study, and the clash of story and tone produces

results that are equally awkward and dull.

C

Steamboat Bill Jr.

(Charles Reisner, USA, 1928, 58 min.)

Viewed on Netflix Second Viewing

This nautical-themed silent comedy is one of Buster Keaton’s

less funny vehicles, but it’s still worth seeing for the stunningly executed

cyclone finale. The climax, nominally

directed by Charles Reisner but obviously choreographed by Keaton himself, is a

marvel of primitive special effects and daring stunt work. It features the best version of Keaton’s most

well-known stunt, in which he is nearly crushed by the falling front of a

house, but the sequence as a whole is so incredible that it’s debatable whether

that’s even the most impressive moment. B-

Ulzana’s Raid

(Robert Aldrich, USA, 1972, 103 min.)

Viewed on Netflix First Viewing

It’s hard to believe that a western this stodgy,

old-fashioned, and openly racist could’ve been released in the era of post-Wild Bunch (1969) anti-westerns, and

it’s especially disheartening to see something this square from Robert Aldrich,

director of the marvelously insouciant Kiss

Me Deadly (1955) and the delightfully insane What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962). D

Wild at Heart (David

Lynch, USA, 1990, 125 min.)

Viewed on YouTube Third Viewing

Full Review at Joyless Creatures

Where Dune (1984)

is an example of what can go wrong when highly idiosyncratic artist David Lynch

is hampered by studio interference, Wild

at Heart shows how disastrous the results can be when the director,

suddenly flush from the success of Blue

Velvet (1986), has the power to put whatever half-formed ideas he can come

up with on the screen. Though

purportedly the tale of a rockabilly couple (Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern) on

the run from a vindictive maternal figure (Dianne Ladd), the film is really an

excuse for Lynch to fulfill whatever violent or sexual whims he couldn’t get

past the censors on the simultaneously produced Twin Peaks TV series. While

Lynch has had great success in other films with sadistic violent content, the

staging of most of that material here is surprisingly pedestrian, as if the

director thought he could make up for an uncharacteristic dearth of intensely

personal details by simply amping up the graphic viscera and nudity. Jokey post-modern references to old Elvis

musicals and The Wizard of Oz (1939)

take the place of Lynch’s usual highly distinctive brand of surrealism, and

Lynch doesn’t have the wit or insight to make ironic detachment work for

him. C-

The Wind Rises

(Hayao Miyazaki, Japan, 2013, 126 min.)

Viewed Theatrically First Viewing

For what will allegedly be his swan song, the great animator

Hayao Miyazaki returns to his lifelong passion for flight with a fictionalized

biography of Jiro Horikoshi, designer of aircrafts that Japan used in

WWII. Though Miyazaki invented most of

the details of Horikoshi’s private life, the film still feels awkwardly

hamstrung by biopic conventions, and goes almost completely off the rails

during a dull stretch where the hero tends to an ailing wife. Structural issues are only part of the

problem with the script, which constantly raises questions about Japan’s

militaristic history only to shrug these issues off in favor of gentle

ruminations about the wonder of flight.

One wonders why Miyazaki gets in to social commentary at all if he’s

going to swerve away from it, or why he chose the biopic form if he was going

to alter so many details of his protagonist’s life (and only come up with a

relatively generic personal story at that).

While this may be Miyazaki’s most problematic film overall, it at least

boasts the charming handmade aesthetic that has always been Studio Ghibli’s

signature. The animation is unfailingly

gorgeous, and the sound design, which includes engine noises that are clearly

being made by people’s mouths, boasts the kind of simple inventiveness that too

many animated films seem to lack. C+

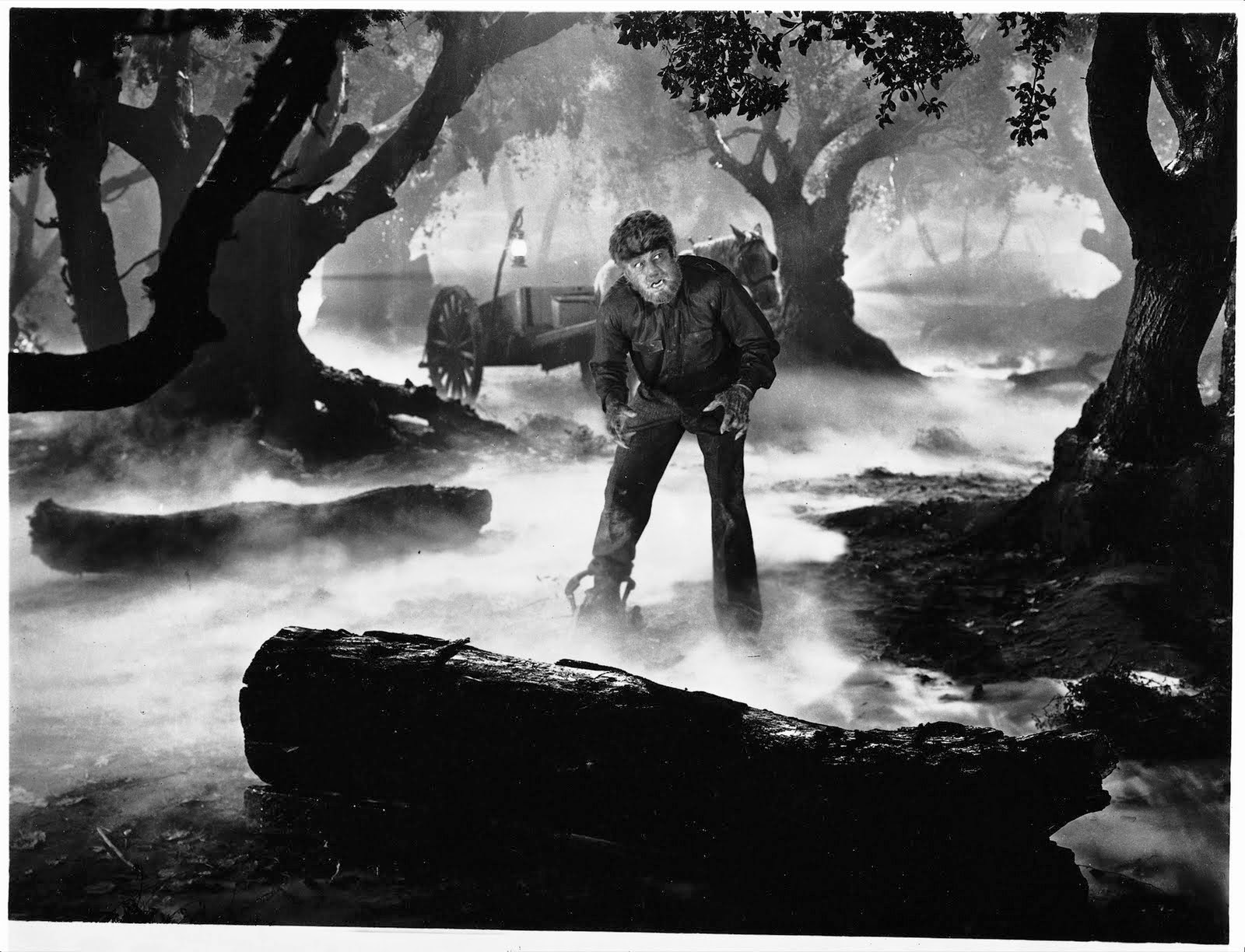

The Wolf Man

(George Waggner, USA, 1941, 70 min.)

Viewed on Netflix Second Viewing

The Wolf Man has

never had the same iconic or allegorical resonance as Dracula (1931) or Frankenstein

(1931), but it still benefits from the timeless production values and

streamlined storytelling of the classic Universal horror house style. Jack Pierce’s makeup effects remain

impressive to this day, and the fog-drenched wood sequences are wonderful showcases

for Joseph Valentine’s black and white cinematography and Jack Otterson’s art

direction. In many ways this is shallow

box-office fodder, but it comes from an era when audiences could rely on generic

blockbusters to be executed with style. B-